The study of thermodynamics is the branch of physics that studies and describes thermodynamic transformations induced by heat and work in a thermodynamic system. These transformations result from processes that involve changes in the state variables of temperature and energy at the macroscopic level.

Classical thermodynamics is based on the concept of a macroscopic system, that is, a portion of mass physically or conceptually separated from the external environment, which is often assumed for convenience to be undisturbed by energy exchange with the system.

The state of a macroscopic system in equilibrium is specified by quantities called thermodynamic variables or state functions, such as temperature, pressure, volume, and chemical composition. The main notations in chemical thermodynamics have been established by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry.

However, there is a branch of thermodynamics, called non-equilibrium thermodynamics, which studies thermodynamic processes characterized by the inability to achieve stable equilibrium conditions.

What does classical thermodynamics study?

Classical thermodynamics focuses on the study of macroscopic systems in equilibrium, using measurable and observable properties. This branch is based on fundamental principles such as the conservation of energy and the laws governing thermal transformations.

In addition to classical thermodynamics, there are other branches that complement its study:

- Statistical Physics : Relates the microscopic properties of particles (atoms and molecules) with observable macroscopic properties, providing a microscopic interpretation of thermodynamic concepts.

- Chemical Thermodynamics : Applies the principles of thermodynamics to the study of chemical reactions and phase changes, analyzing how energy and entropy influence the direction and equilibrium of chemical processes.

- Equilibrium thermodynamics : Focuses on systems that reach a state of thermodynamic equilibrium, analyzing the conditions under which matter and energy transfers occur in these systems.

- Non-equilibrium thermodynamics : Studies systems that are not in thermodynamic equilibrium, addressing irreversible processes and fluctuations that occur outside of equilibrium.

Laws of classical thermodynamics

The principles of thermodynamics were established during the 19th century and govern thermodynamic transformations, their progress, and their limits. They are real, unproven, and unprovable axioms, based on experience, upon which the entire theory of thermodynamics is based.

We can distinguish three basic principles, plus a "zero" principle that defines temperature and is implicit in the other three.

Zeroth law of thermodynamics

When two interacting systems are in thermal equilibrium, they share certain properties, which can be measured, giving them a precise numerical value. As a result, when two systems are in thermal equilibrium with a third, they are in equilibrium with each other, and the shared property is temperature.

The zeroth law of thermodynamics simply states that if a body "A" is in thermal equilibrium with a body "B" and "B" is in thermal equilibrium with a body "C", then "A" and "C" are in thermal equilibrium with each other.

This principle explains the fact that two bodies at different temperatures, between which heat is exchanged (even if this concept is not present in the zero principle) end up reaching the same temperature.

First law of thermodynamics

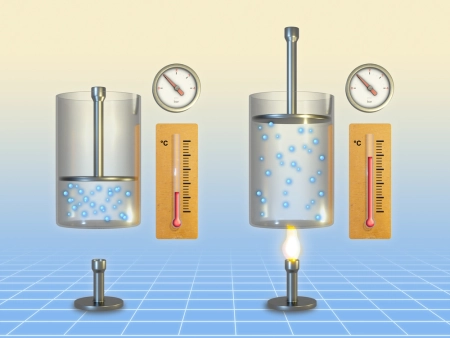

The first law of classical thermodynamics, also known as the principle of conservation of energy, states that the total energy of an isolated system is conserved. In other words, energy cannot be created or destroyed; it can only be transformed from one form to another.

The mathematical formulation of the first law of thermodynamics is:

\[\Delta U = Q - W\]

where ΔU represents the variation in the internal energy of the system, Q is the heat transferred to the system from the surroundings and W is the work done by the system on the surroundings.

This equation indicates that any change in the internal energy of a system is due to heat transfer and work done. If Q is positive, it means that heat is being supplied to the system, while if it is negative, the system is releasing heat to the surroundings. Similarly, if W is positive, it indicates that the system is doing work on the surroundings, and if it is negative, the surroundings are doing work on the system.

Second law of thermodynamics

There are several statements of the second law, all equivalent, each formulation emphasizing a particular aspect. It states that "it is impossible to realize a cyclic machine which has as its sole result the transfer of heat from a cold to a warm body" (Clausius statement) or, equivalently, that "it is impossible to carry out a transformation whose sole result is to convert the heat extracted from a single source into mechanical work" (Kelvin statement).

This last limitation denies the possibility of so-called perpetual motion of the second kind. The total entropy of an isolated system remains unchanged when a reversible transformation occurs and increases when an irreversible transformation occurs.

Third law of thermodynamics

The third law of classical thermodynamics states that absolute zero (0 Kelvin) cannot be reached by a finite number of thermodynamic transformations. This law was formulated by Walther Nernst in 1906.

More precisely, the third law states that the entropy of a pure, perfectly crystalline system is zero when the temperature reaches absolute zero. Entropy is a measure of the disorder or randomness of a system, and the third law indicates that as the temperature approaches absolute zero, the entropy of the system also tends to zero.

Applications of classical thermodynamics

Classical thermodynamics has a wide range of practical applications. Below are some of the areas in which classical thermodynamics is widely used:

- Power Engineering: Classical thermodynamics is essential for the design and optimization of power generation systems, such as power plants, gas turbines, internal combustion engines, and renewable energy systems. It helps us understand energy efficiency, thermodynamic cycles, and heat transfer in these systems.

- Chemical Engineering: Classical thermodynamics is crucial for the design and operation of chemical processes, including chemical production, petroleum refining, materials synthesis, and food production. It enables the analysis of chemical equilibria, heat transfer calculations, and process optimization.

- Refrigeration and Air Conditioning: Classical thermodynamics is essential for understanding refrigeration cycles and air conditioning systems. It aids in the design of refrigeration systems, the selection of refrigerants, and the calculation of cooling capacity.

- Materials Science: Classical thermodynamics is used to study the properties of materials in different thermodynamic states, such as solid, liquid, and gas. It helps predict phase stability, phase transitions, and equilibrium properties, such as vapor pressure and solubility.

- Study of chemical equilibrium: Classical thermodynamics is fundamental to understanding chemical equilibrium and the behavior of chemical reactions. It allows us to determine whether a reaction is spontaneous or not and provides information about the thermodynamic performance of chemical processes.

- Atmospheric and Climate Research: Classical thermodynamics is applied in the study of the atmosphere, climate, and meteorological phenomena. It helps us understand the processes of heat transfer in the atmosphere, cloud formation, and solar radiation.